The Watson School's IJC Assistant Professor of Economics and International and Public Affairs, Bryce Millett Steinberg, along with research collaborators Natalie Bau, Martin Rotemberg and Manisha Shah, recently published a working paper, "Human Capital Investment in the Presence of Child Labor," at the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Steinberg's research centers around the question of how families and individuals make decisions about investment in human capital in the developing world, and how market forces, government programs and behavioral biases can impact these decisions. With this paper, Steinberg and her team ask whether parents in places with high child labor rates reinforce early childhood and prenatal human capital investments to increase schooling.

In their research, the team exploited the fact that early life rainfall creates an external shock to initial human capital. Because increased rainfall leads to greater crop yields and, by extension, better childhood nutrition, it affects factors such as height and early test scores. A large body of research shows that increased early-life rainfall and human capital investment between the ages of zero and five — when the human brain is most plastic — lead to increased schooling.

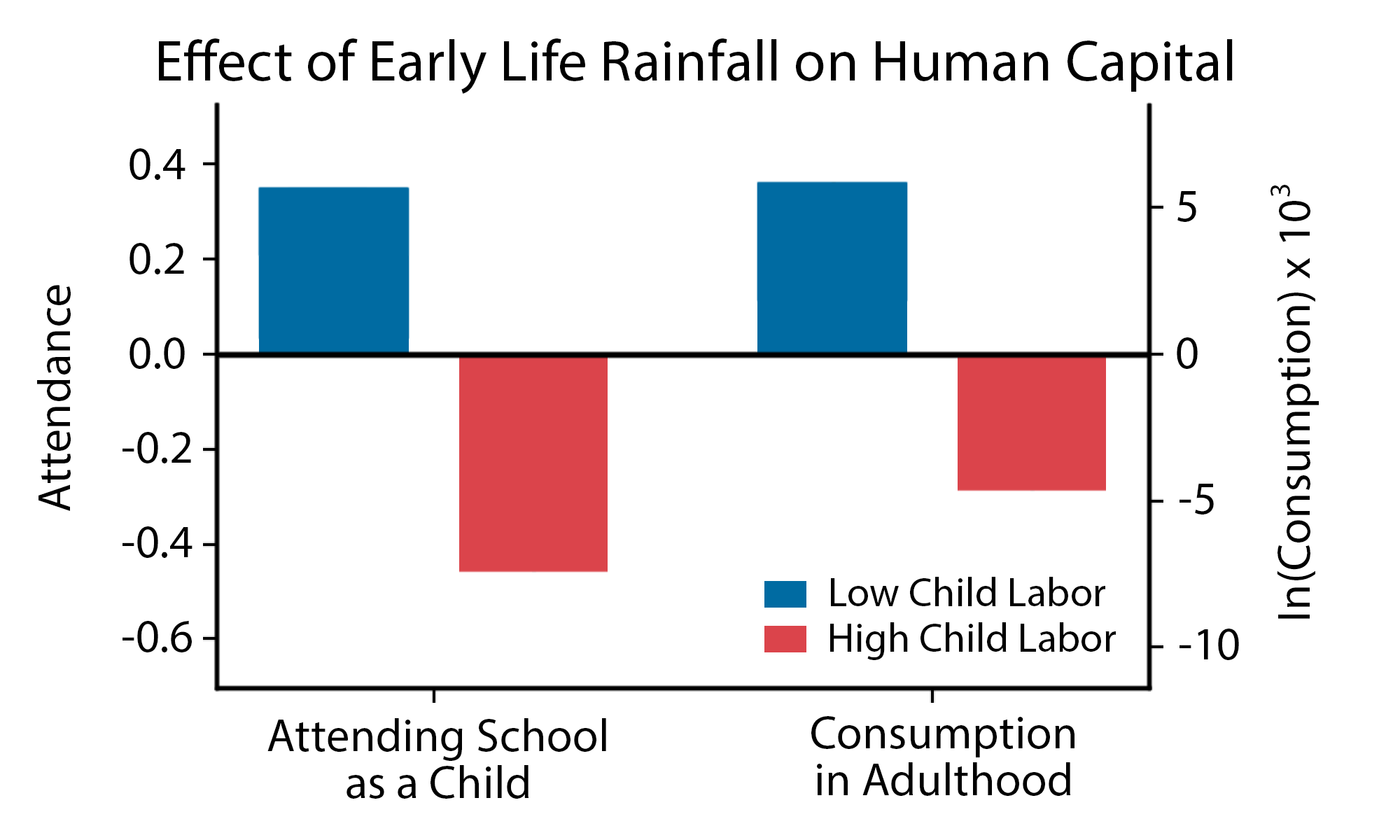

Steinberg said, "There have been a lot of studies that demonstrate the benefits of early childhood interventions, but most of that research has been conducted in developed countries that don't have a lot of child labor." The team wanted to know if the same benefits accrued in places with high child labor rates. What they found was that the opposite was true. Early childhood interventions actually result in a reduced level of education in areas with high child labor rates.

"One of the lessons of development economics," she said, "is that you cannot just take policy models from rich countries and apply them to India or Sub-Saharan Africa without thinking through the context." According to Steinberg, the same early childhood investments that help children perform better in school also make them better workers. So, in places with a high percentage of child labor, "parents might choose to use that human capital by putting their children to work instead of keeping them in school." Overall, the researchers found that in these places, children with positive human capital shocks early in life are less likely to stay in school and more likely to be working.

The research team found this same pattern at work across three different nationally representative data sets and several independently measured outcomes. They also found that these effects persist into adulthood and that households whose heads experienced positive early-life shocks in high child-labor districts consume less per capita than those that did not. Steinberg said, “This is evidence that, remarkably, children can be made worse off by a positive income shock in early childhood in places where there is a market for children's labor.”

This research was funded in part by the Orlando Bravo Center for Economic Research.