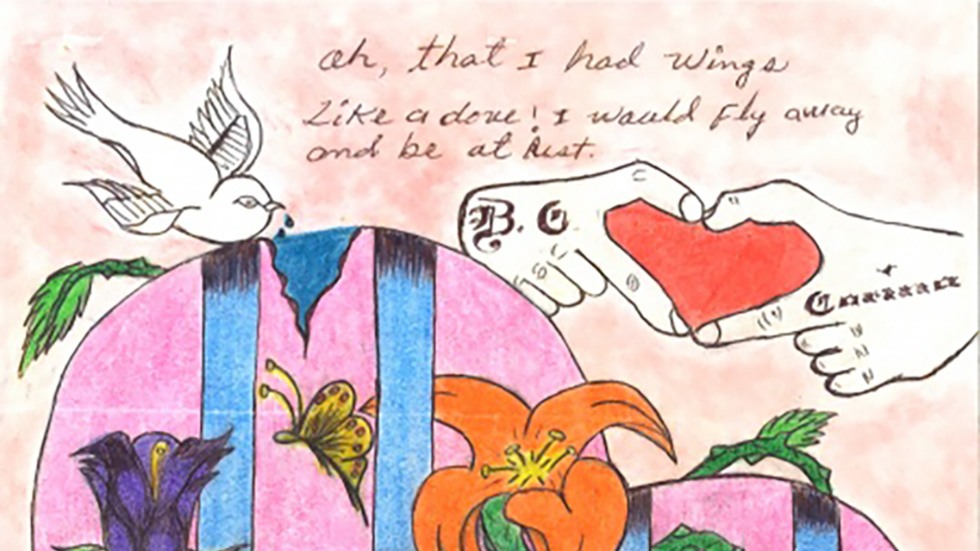

Comprising letters, artwork, and objects created by people detained at SDC, the exhibition evokes themes of repressive detention conditions, memories of life before experiencing immigration enforcement, and hope for a future free from institutional violence, “Breaking Out” is the project of Kristen Kolenz, a postdoctoral fellow at Watson’s Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies (CLACS) and co-curators Sarah Baldwin and Carl Smith in collaboration with Art at Watson. The artworks, created under surveillance, were sent to El Refugio in Atlanta, GA. From them, Kolenz, who has previously worked with El Refugio, curated a collection of borrowed items. The documents and artifacts, often creased and stained, contain pleas for help – for clothes, for legal representation, for asylum support – and depict details of the creators’ daily lives, both before and during their detentions.

The Mellon Sawyer Seminar offers opportunities

In 2020, in collaboration with the Center for the Study of Slavery and Justice and the Africana Studies Department, CLACS submitted a proposal to the Mellon Foundation for its Mellon Sawyer Seminar for “Rethinking the Dynamic Interplay of Migration, Race, Ethnicity in the Caribbean and Latin America.” The proposal was awarded a Mellon Foundation Sawyer Seminar grant of $225,000 for 2021-22. Due to the pandemic, the Seminar, normally a one-year event, will run through 2023.

The grant, which funds Kolenz’s fellowship and two graduate students, also supports this exhibition and other programs, including the upcoming “Histories of Migration and Violence in Latin America and the Caribbean,” a hybrid conference (scheduled for March 17-18. Kolenz’s project depicting the lives of detainees who experienced forced migrations from these regions is an integral part of the current Mellon Foundation Sawyer Seminar, says Senior Fellow and CLACS Director Patsy Lewis.

“This exhibit is an opportunity to let people in detention speak for themselves about the conditions of their own lives,” says Kolenz, who acknowledges that, as a white woman from Ohio, she does not share the experiences of the people she studies. “How do I amplify the struggle and the way people are transforming the world to a place that they want to live in?”

“These letters,” says Director of Undergraduate Studies and Visiting Associate Professor of Latin American and Caribbean Studies Erica Durante, “are the only links they have with the external world and … become the only piece of freedom that still remains. We want to build the memory of what is otherwise completely silenced. Each letter is an intense, condensed story that represents the letter writer and the family behind him.”

Calling this exhibition “an embodied approach to knowledge,” Kolenz says, “We’re working with those materials directly – from the hands that draw the images or write the letters. We’re going straight to a source that’s difficult to get to.” Because a high percentage of immigrant detainees are deported to their home countries, Kolenz notes that they are lost to us when they are gone. Nevertheless, their letters and artwork offer a trace of what these detainees experienced in U.S. detention. This exhibition, she says, “is a reminder to follow those traces back.”

Acknowledging that many Brown students are personally familiar with immigrant detention experiences, Kolenz adds, “We must find a way to figure out what these immigrants’ detentions mean to us, depending on where we stand in relation to them.”

For Durante, an Art at Watson member and co-curator of “Breaking Out,” the exhibition is a valuable opportunity to raise Brown community’s awareness about the situations facing migrants arriving in the United States and to bring detainees’ otherwise anonymous voices directly to human rights activists.

“Many students, staff, and faculty at Brown are activists at the U.S.-Mexican border, and Latinx community members and students from the diaspora do a lot of field work in Providence with vulnerable Latinx communities here,” says Durante. “There is no distance in time and space in what detainees are recounting and what’s happening today. We can’t dissociate ourselves from this.”

The crisis continues even when it’s not in the news

With few “lightning rod” immigration issues currently dominating the news media, Kolenz hopes that this exhibition will remind people that these highly vulnerable populations are being detained all the time. Durante and Kolenz say conditions at SDC, whose 1,966 beds are almost always filled, are brutal: poor access to healthy food; experiences of physical violence and torture; and deprivation of essential medical care. Irregularly documented immigrants are incarcerated at several comparable institutions across the United States.

“These materials allow people detained at Stewart Detention Center to speak in their own terms about their experiences,” says Kolenz. “I want people to engage with those who have been detained.”

Lewis agrees: “Migration… is very much an academic subject. As researchers, we put distance between the subjects and ourselves,” she says. “These are not just academic questions we’re examining; we’re responsible for the individuals whose lives are affected by policies. I hope the exhibition reminds us that these are people’s lives.”